End of the rainbow: sex, empire, and the new right

Alex Stoffel •Alex Stoffel, author of Eros and Empire, traces how liberal narratives that once instrumentalised LGBTQ+ rights as markers of modernity have given way to a resurgent right-wing politics, where sexuality becomes a site of fear, control and civilisational anxiety.

Queer and trans people have emerged as some of the most reliable and visible proponents of Palestinian freedom in Global North states. Within universities, gender studies departments were among those who released the most principled statements after the 7 October attacks. At marches and mobilisations, queer and trans people have been visibly over-represented since the beginning of the genocide. And an increasingly small minority of the wider LGBTQ+ public are duped by pinkwashing campaigns. Israeli Hasbara that targets LGBTQ+ people reads to most people as played out and corny. As Sita Balani pointed out on our panel at the Festival of the Oppressed, pinkwashing and homonationalism is now a hallmark of right-wing trolls on social media, rather than of state leaders and multilateral organisations. This is a huge success — especially considering that LGBTQ+ people were among the most propagandised communities throughout the global war on terror — for which we have the tireless efforts of anti-imperialist and anti-war queer activists and writers to thank.

How did we get here? With the onset of the global war on terror in the early years of the 21st century came a wave of reactionary gender and sexual politics. First, there was a rehashing of many gendered colonial narratives. Western civilising missions have often involved the discourse of what Gayatri Spivak once called ‘white men saving brown women from brown men.’ This phrase encapsulates the paternalistic and imperialist attitude historically exhibited by Western colonisers, who justified their imperial conquests and rule by claiming that they were bringing ‘civilisation’ to ‘barbaric’ lands. A key part of this narrative involved presenting themselves as protectors and saviors of oppressed women in these societies. This phrase became relevant once again in the context of the war on terror as Western nations justified their military invasions, occupations, and counter-insurgency operations by framing them as efforts to rescue women from the perceived barbarism of their native cultures. It goes without saying that Western militaries did not rescue Afghan and Iraqi women. The war on terror brought terror to their lives.

When it comes to sexuality, something different seems to be happening. Rather than ramping up the repression of LGBTQ+ people at home, Western states began to extend rights and representation to (white and middle-class) gay and lesbian citizens at a historically unparalleled speed. Sexual minorities that had until very recently been considered deviant were now being recast as patriots and respectable citizens.

At the very same time that sections of the LGBTQ+ community were winning legal victories and being included within the national imaginary for the first time, Islamophobic violence was on the rise. New technologies of surveillance, segregation, deportation, exclusion, and death were being instituted by those same states. Queer scholars and activists began to point out that this was no coincidence. The term ‘homonationalism’ rose to popularity to describe the relationship between these two processes: how the acceptance of LGBTQ+ identities was leveraged to justify exclusionary policies, and how the legal and representational inclusion of some LGBTQ+ subjects was predicated on the pathologisation of racialised populations, embodied by the figure of the male Muslim terrorist. In this way, the extension of rights to LGBTQ+ people became part of the imperialist agenda of Western nations. It was a Faustian bargain that allowed Western states to win over the support of many gays and lesbians for their imperialist wars.

At first, homonationalism may appear as discontinuous with the sexual politics of the earlier colonial era, but it actually turns out to be a mere inversion. While during the colonial era colonised populations were stigmatised on the basis of being ‘too queer’ (because they exhibited deviant family structures, wayward sexual practices, unfamiliar parenting customs, and so on), during the war on terror, Arab cultures were stigmatised on the basis of being ‘not queer enough’ (hypermasculine, excessively patriarchal, and so on). In both cases, civilisational hierarchies are upheld through distinctions between the ‘proper’ gender and sexual norms of Western nations and the ‘backward’ gender and sexual cultures of non-Western nations. The latter is taken as ‘proof’ of those groups’ inability to govern themselves.

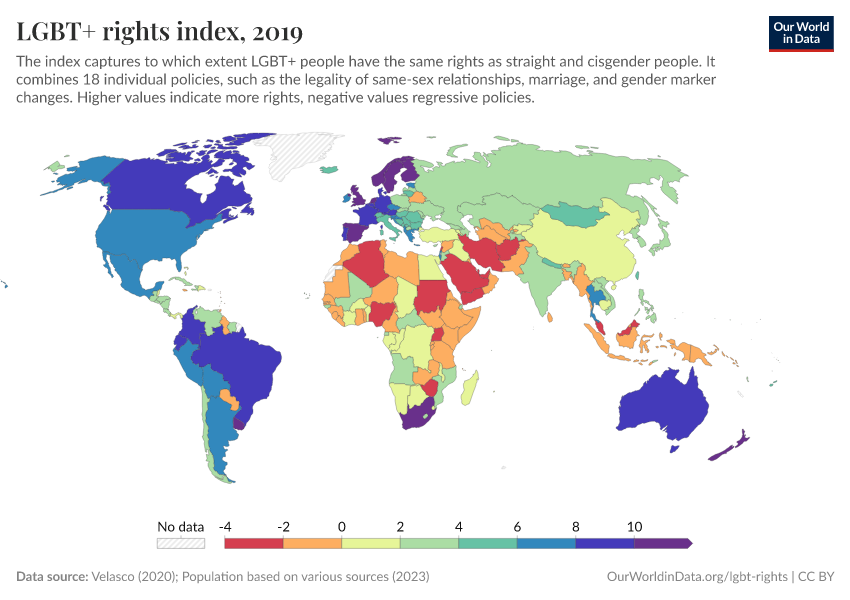

One very explicit application of homonationalist discourse was found in the many maps, drawn up during the war on terror, that ranked states around the globe according to the rights and protections they afforded LGBTQ+ people. These indexes used LGBTQ+ rights as a barometer for measuring how ‘modern’ or ‘progressive’ states were.

If homonationalism once cloaked Western imperialism in rainbow hues, the new global right offers a very different, yet equally dangerous, sexual politics. The time is over when Western states promised (and indeed granted) various protections to LGBTQ+ people in return for their support for their imperial agendas. Today, the ruling parties of those same states are rolling back protections for those same minorities, allying themselves with anti-gender activists, and stoking vicious moral panics about trans people. We’re living in a mask-off moment, when even the pretense of LGBTQ+ acceptance is quickly being abandoned. This raises the question: What comes after the liberal international order? What is the new global sexual politics of the right?

The international politics of prominent far-right intellectuals today is characterised by a hostility towards what they perceive to be the universalising and homogenising processes of liberalism and capitalism. The right sees globalisation as a force that corrupts national economies, imposes sameness upon ‘naturally’ distinct ethnic cultures, and erodes the traditional institutions of church, nation and family. It proposes, instead, a political model that is often referred to as ‘ethnopluralism.’ Ethnopluralism posits that the world consists of multiple, coexisting ethno-cultural regions and advocates for the preservation of the boundaries between them.

For the right, the universalising tendencies of liberal capitalism are most effectively challenged through the recognition and affirmation of distinct ethnic and cultural identities. As Miri Davidson explains, ‘the preservation of anthropological difference and a sense of indigenous fragility are common tropes on the European far right.’ The right holds a view of the international sphere as a tapestry of organic/natural ethno-cultural groups that are divided along regional lines. It differs from liberal multiculturalism in its emphasis on the maintenance of clear territorial demarcations between these distinct groups.

It remains to be seen to what extent far-right thought will meaningfully shape the foreign agendas of contemporary ruling parties. While this influence seems particularly manifest in the discourse of state leaders like Vladimir Putin or Georgia Meloni, it is unclear whether it plays a material role for the current Trump administration. Nevertheless, we do see early indications that it does. For example, in May 2025, after embarking on a four-day tour of the Arabian Peninsula to secure investments deals, US president Donald Trump shared a clip on X (formerly Twitter) in which he recapped:

The gleaming marbles of Riyadh and Abu Dhabi were not created by the so-called nation builders, neo-cons, or liberal nonprofits. The birth of a modern Middle East has been brought by the people of the region themselves. Peace, prosperity, and progress ultimately came not from a radical rejection of your heritage, but rather from embracing your national traditions and embracing that same heritage that you love so dearly.

Gone is the war on terror’s rhetoric of ‘exporting democracy and freedom to the Middle East.’ In its place is an affirmation for cultural ‘authenticity’ that reinscribes patriarchal rule. The video presents a view of global order in which regions such as the Middle East achieve modernity and prosperity not through the adoption of ‘American’ values but through the embrace of their own national traditions and heritage. This worldview stands diametrically opposed to the homonationalist discourses of the global war on terror, where LGBTQ+ rights were instrumentalised as barometers of modernity and civilisation. Here, it is essentialised notions of tradition and cultural heritage (to which we could no doubt include patriarchal gender and sexual norms) that serve as civilisational standards.

What role can we expect sexuality to play in this ethnopluralist vision of the world? In a 2024 interview about JD Vance and MAGA Republicanism, sociologist Melinda Cooper observed that the dominant line of sexual deviance is shifting. It’s no longer primarily between heterosexual and homosexual, but between those who can reproduce and those who cannot or choose not to. This is, I think, a useful way of thinking about how sexuality is being reframed in today’s global politics. An ethnopluralist worldview imagines the globe as divided into distinct ethno-cultural groups (read: races), each with its own heritage to protect and preserve. Within this logic, ensuring the survival of the group becomes a political imperative, and that means controlling who reproduces, how they reproduce, and under what conditions. Projects that claim to defend the ‘integrity’ of an ethnic group or national culture often turn to controlling women’s sexuality and persecuting sexual and gender minorities. In this vision, women and queer people become existential threats: their freedom to live, love, and form families on their own terms is seen as a danger to the group’s biological continuity. If reproduction is sacred, then any disruption to it (whether through abortion, queerness, or gender nonconformity) is treated as a threat to the future. That’s why the far right targets gender and sexuality so aggressively: because, to them, freedom in these realms endangers the very survival of the imagined nation.

This concern with racial reproduction helps us explain how the heteropatriarchal domestic agendas of anti-abortion politics, extreme pro-natalism, and transphobic cultural wars comport with the wider construction of a new international order. Far-right nationalist movements have installed the figure of the ‘biological woman’ – defined primarily by her capacity for reproduction (that is, her ability to become pregnant) – at the center of their political imaginary. They have also appointed themselves as the protectors of children, icons of the nation’s future, by stoking cultural anxieties about the imaged threats trans people pose to reproduction (through grooming, pedophilia, or forced sterilisation). Gender and sexual politics are no longer side skirmishes in the culture wars: they are central battlegrounds in the far right’s vision for a racially ordered world.

The rainbow mask of liberal inclusion has fallen. What remains is a global right-wing project that sees queerness not as a threat to decency, but as a threat to racial survival. If homonationalism offered queers a place in the empire, today’s right offers only erasure.

0 comments