Breaking the state

DK Renton •

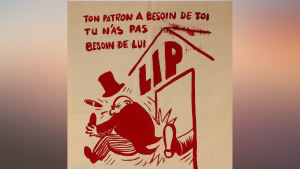

In his final article on rs21’s key political ideas, DK Renton explains why we can’t take over the state – we need to smash it to create a new world of freedom

The point at which revolutionaries and reformists have distinguished themselves most clearly is in our respective attitudes to the state. The reformist path to socialism based itself, historically, on the insistence that large parts of the state could be repurposed and used to improve the lives of the majority. For the post war Labour government of 1945-51, the enemies were as follows. ‘Want’: too many workers were in poverty, therefore benefits would be introduced and raised to ensure that no-one went without food or clothing. ‘Disease’: a national health service would be introduced, free at the point of delivery and not for profit. ‘Ignorance’: schools would give all children useful knowledge that would offer working class families in particular a chance to ascend. There was no good reason why someone born to a middle-class family should have privileged access to the highest-paid professional jobs; rather they should be open to all. ‘Squalor’: the state would own homes, in a good condition, and rent them out cheaply to millions of working-class tenants. ‘Idleness’: the state would promote work schemes to ensure that never again were people left without work.

Little of this programme remains part of the reformist mindset. Benefits are not being raised. The NHS has become in politicians’ minds a terrain of opportunity for the rich: its data is sold off. The state has been repurposed to protect the rich. The purpose of comprehensive schooling is lost; how could it survive in a world where jobs themselves are not allocated by skill, and where ownership of assets, rather than employment is the quickest way to get rich? There will be no increase under Labour in social housing. Reformists are intensely comfortable with our world of underemployment and unemployment and casual working – all these devices prevent the greater danger, the rebirth of working-class power. Social democrats have given up believing in reforms, and in the generous potential of the state.

The revolutionary critique of capitalism was founded on a different appraisal of the same institutions. From the birth of the first revolutionary parties in the 1880s and onwards, previous generations of revolutionaries warned that you could not simply take over the state and use it as if it was neutral. Even its most progressive elements were governed not by politicians but by senior civil servants who had their jobs for life, who saw the poor and racial minorities as hostile others, who would administer these systems in a spirit of charitable good grace rather than seeing them as institutions which workers themselves might run.

Revolutionaries warned of the dominance of society by institutions which Labour never dared touch: the monarchy, the House of Lords, the public schools.

They spoke also of the many other parts of the state which were not there to help the poor or even to ensure that capitalism created new workers in each generation. They warned of the state’s authoritarian elements – the police, immigration officers, the role that the army played in putting down revolts in the British empire and as a backstop behind capitalist power at home. They argued for the reduction of the power of unelected judges, and of all aspects of the carceral state – the abolition of the army, of prisons, of law.

The revolutionary theorist who best conveys this challenge to the state is Vladimir Lenin, in his pamphlet, The State and Revolution. Written in summer 1917 in the middle of a year of tumultuous struggles, and at a time when his party, the Bolsheviks, were winning majority support among Russian’s urban workers, Lenin was calling on his comrades to stop thinking just about working-class struggle, but to reflect instead on what came at its end-point: what kind of power should revolutionaries wield once we’d won?

He began with the last moment when an insurrection had taken power and held it for any meaningful time – the Paris Commune of 1871. The Communards determined that all elected officials should hold their roles only for so long as they were accountable to their electors, any official who overstayed their mandate should be subject to recall. They insisted on the abolition of the standing army and its replacement by a popular militia.

Important as each of these demands both were, Lenin insisted that they were just a means towards a different idea of government: in which no officials would have privileges over the people they governed, workers would run everything.

Under Communism, ‘We, the workers,’ Lenin wrote, ‘shall organise large-scale production on the basis of what capitalism has already created, relying on our own experience.’

There would be no administrative state, or not in the sense that the reformists understood it.

We shall reduce the role of state officials to that of simply carrying out our instructions as responsible, revocable, modestly paid ‘foremen and accountants’ (of course, with the aid of technicians of all sorts, types, and degrees). This is our proletarian task, this is what we can and must start with in accomplishing the proletarian revolution.

Communism would mean the progressive destruction of all that constituted the state and its bureaucracy:

Such a beginning, on the basis of large-scale production, will of itself lead to the gradual ‘withering away’ of all bureaucracy, to the gradual creation of an order … under which the functions of control and accounting, becoming more and more simple, will be performed by each in turn, will then become a habit and will finally die out as the special functions of a special section of the population.

Trying to explain and simplify this idea, 40 years later, the Trinidadian revolutionary C. L. R. James put it as follows: ‘Every Cook Can Govern.’

The form identified by Lenin, and his fellow Bolsheviks, as capable of instituting a change to direct workers’ rule, were the soviets or workers’ councils. The first of these had been founded in St Petersburg in the previous Russian Revolution of 1905. It began life as a talking-shop, a meeting place for all the city’s radicals, a chance where they could swap ideas for how to keep the revolution spreading. At the start of 1917, its base had widened. It had become the place to which all revolutionaries went if they were going to distribute resources. How would they answer the demands of factories for material? Would the revolutionary soldiers be paid? As the model of workers’ councils spread throughout Russian, so you also needed collectives to represent every part of each, each town, each workplace – to negotiate between groups of producers, and between the producers and their neighbours who relied on them.

Lenin’s idea of abolishing the state offered much to Russia’s poor and the oppressed. Read the petitions sent to the Soviet by groups of workers in that year, and what they complain of are the humiliations imposed on them by their bosses, backed up by the state. They called for a shorter working week, better pay, the removal of foremen and secret policemen, and the end of bosses’ power to fine. Tsarist Russia treated workers as servants, imposed strict criminal penalties on workers who left their employment or disregarded workplace rules. You could not transform relationships in the workplaces without changing – abolishing – the law.

What was true of workers, was even more true for other oppressed Russians. In a spirit of hope, consistent with the early dreams of the revolution, no-fault divorce was introduced. All ideas of legitimacy in birth were discouraged. Married couples could take either surname. Women were granted rights to earn a wage, seek education, exchange property.

By the simple act of abolishing the Russian penal code, the USSR took male same-sex relations out of the criminal sphere. There had been, it is worth acknowledging, little debate in Russia about whether homosexuality should be permitted. There was no consensus within the Bolshevik party in favour of abolition, no gay counterpart to such militant campaigns as the Communist women’s section, Zhenotdel. Simply, the decision to take these questions out of the world of the law and the state was enough to achieve a very great deal of liberation – because it was the state which disciplined while Russian society was content to live and let live. Decriminalisation created the conditions for spreading tolerance. The weakening of the courts, prisons and the law took on a logic of its own.

The demand to abolish the existing state has been part of every revolutionary project worthy of that name since Lenin’s day: from the revolutionary workers in the National Union of Railwaymen and the South Wales Miners’ Federation who sent letters of support for Radclyffe Hall when her queer novel The Well of Loneliness was prosecuted in 1928, to the anti-war protesters in the United States, 40 years later during the trial of the Chicago 7, who fought back against the court prosecuting them, unfurling Vietcong flags, blowing kisses at their Judge, dressing in black judicial robes beneath which were hidden police uniforms.

In Germany in the 1970s, a Socialist Patients’ Collective or SPK argued that even our health systems needed to be broken down, and a new model built on its ruins. The demand for perfect health was a ‘fantasy’, they wrote, a way of pathologising drug use, homosexuality, mental or physical disability. They called for a different kind of healthcare, ‘no longer concealing the social conditions and social functions of illness’ but confronting them.

When Karl Marx put the case for revolution, he presented it as a great act of mutual cleansing. The revolution was ‘necessary’ he wrote, not only because the ruling class cannot be overthrown in any other way, but also because the class overturning it can ‘only in a revolution succeed in ridding itself of all the muck of ages and become fitted to found society anew.’ He had, in other words, an idea of people changing themselves, of becoming the best that we could be. That task would be, necessarily an act of will – the culmination of many people’s journeys from reluctant critics to full-on enemies of the system.

In other words our rulers keep their grip over us through their control of ideas. Only if we learned to shed the chains we have inside our own heads could we, collectively, take power. To do that, we would have to unlearn so much that we had been taught: the selfishness, the bigotry that capitalism insinuates inside all our heads.

The most important thing we would all have to unlearn was the idea that we ourselves are powerless, that some elites of approved officials or the rich must keep their power over us. The alternative that revolutionaries offer to the power of the state is our democracy, our ideas, our strength. We believe that workers have such knowledge of society that we could run the world ourselves. We do not need leaders, police or bureaucrats; the vision of socialism is not in the end any more difficult or complex than that.

0 comments