Red Friday – why workplace organising outdoes left union officials

Andrew Stone •Many on the left look to a strategy of electing left leaders, including left union leaders. But events of a hundred years ago show that organising from below, in workplaces and communities, wins much more, as Andrew Stone describes.

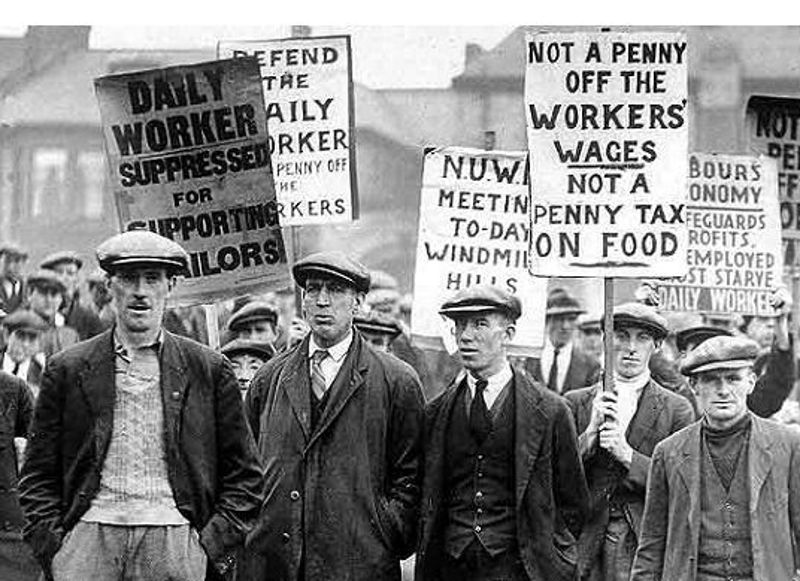

‘The greatest victory in Labour’s history’ proclaimed the Daily Herald, the then official newspaper of the Trades Union Congress (TUC), of the events of 31 July 1925. ‘The manifestation of solidarity which has been exhibited by all sections of the trade union movement is a striking portent for the future and marks an epoch in the history of the Movement’ gushed a letter from the TUC to its secretaries. But we are unlikely to see balloons and bunting for a centenary celebration, as in reality the apparent governmental climbdown merely delayed a conflict that would eventually break out in the General Strike of May 1926. While the dispute centred on a battle with the miners, a group then 1.2 million-strong but now consigned to economic obscurity, this is still a conflict with lessons for trade union and political organising today.

Some context on the terrain of class struggle is necessary. In the 19th century the British trade union movement had been dominated, politically if not numerically, by conservative craft-based unions that retained features of exclusivist medieval guilds. The latter stages of the industrial revolution created larger and more interconnected workforces, giving space for semi- and un-skilled workers (such as gas workers, matchmakers and dockers) to struggle in much more militant fashion under the banner of ‘new unionism’ from the late 1880s. A successful campaign for a 10 per cent wage demand also led to the consolidation of county-based miners’ unions into the Miners Federation of Great Britain (MFGB), which would organise the large majority of the industry thereafter.

The employers and the state were not slow in counter-attacking though, and the Taff Vale judgement of July 1901 was a key weapon used to undermine trade union activism. It centred on a strike provoked by the victimisation of John Ewington, a railway worker, which led to the greasing of rails and decoupling of carriages carried out by striking workers. The court, and later the House of Lords (the highest court of appeal prior to the creation of the Supreme Court in 2009), deemed the union – and therefore by precedent, all unions in future – liable for damages inflicted on an employer during a strike. The desire to challenge this legal cosh fuelled the trade union bureaucracy’s support for the nascent Labour Party (still at this time known as the Labour Representation Committee, with only 2 MPs). It’s an interesting irony, as David Renton points out, that it was acts of sabotage that the current Labour government would probably consider proscribing as terrorism that led to its own party’s emergence.

This judgement was ultimately overturned by the subsequent Liberal government, but what it established institutionally remained: the trade union bureaucracy’s separation of industrial struggle – to be pursued wherever possible through persuasion and arbitration with the employers, with the strike weapon a ‘last resort’ to strengthen its bargaining position – and the movement’s political representation through Labour in parliament. It was a false dichotomy that would frequently weaken workers’ struggle on both fronts.

1910 – the Great Unrest

Although reformism was to be boosted in the long term, in 1910 a fresh wave of struggles broke out that would become known as the Great Unrest. Just as women match workers had lit the fuse of new unionism in 1888, it was women chainmakers (initially 300, swelling to 800 during the dispute) in Cradley Heath in the West Midlands who took the lead with a two-month strike that encouraged massive solidarity and earned many involved a doubling of their previously meagre pay.

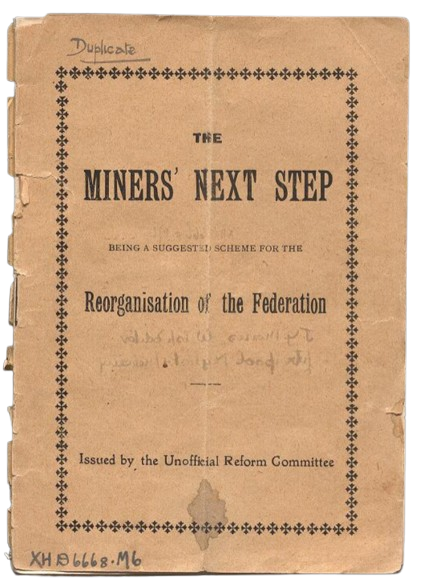

A much larger dispute engulfed the South Wales coalfields in September, when the lock out of 800 miners led to the South Wales Miners Federation (SWMF) calling out 12,000 men, which grew to 30,000 by December. The police and the army were sent in by Home Secretary Winston Churchill to protect scabs and attack the strikers. One striker, Samuel Rays, was killed and 300 extra police batons were sent to replace those broken over the heads of the miners. While the SWMF leadership eventually brokered an unnecessary surrender, many miners drew radical, if not fully revolutionary, conclusions. These were best articulated by the newly created Unofficial Reform Committee, with a syndicalist policy that sought to organise on a rank and file basis co-ordinated within and across whole industries. Its pamphlet, The Miners’ Next Step, argued for a policy that took power away from the ‘professional’ trade union bureaucracy and ‘to build up an organisation that will ultimately take over the mining industry, and carry it on in the interest of the workers.’

Between 1905-09, official figures record 456 strikes in Britain involving 144,000 workers. Yet by 1912 there were 857 strikes involving 1,233,000 workers, almost a tenfold increase in a fifth of the time, with almost 41 million strike days. 1911 produced the first national railway strike – much to the consternation of the National Union of Railwaymen’s (NUR) reactionary ‘leader’ JH Thomas – and 1912 the first national miners’ strike. This six-week battle forced the government to pass the Minimum Wage Act, which protected miners from the worst excesses of payment by ‘piece rates’, which were often highly variable by location. The militancy that characterised many of these disputes, often running far ahead of their trade union executives, recruited by 1914 some 2 million extra members to the 2.5 million of 1909. Many were involved in active fundraising for struggles such as the Dublin Lockout of 1913, which raised £150,000 in donations (the equivalent of £15 million today). But Labour leaders and trade union leaders quelled the potential for solidarity action that could have won that dispute, and they overwhelmingly supplemented the jingoistic state authoritarianism that accompanied the outbreak of the First World War (Ramsay MacDonald made token anti-war noises and was replaced as Labour leader by Arthur Henderson, who joined the coalition government with Liberals and Tories).

Workplace and community struggles in World War One

The slump in class struggle was not sustained though, with wartime conditions worsening living standards. The illegality of strikes did not prevent their recurrence – it tended instead to see them bypass trade union officialdom once again. In this context the independent role of shop stewards (local workplace reps) increased, and combined with (female-led) local tenants organisation underpinned the struggles on ‘Red Clydeside’. A rent strike involving 20,000 residents threatened to spread throughout the country, forcing the government to legislate to freeze rents for the rest of the war. And the Clyde Workers Committee (CWC) was formed in response to attacks on working conditions, with a justly famous manifesto that promised ‘that we will support the officials just so long as they rightly represent the workers, but we will act independently immediately they misrepresent them.’ When in January 1919 Glasgow engineering workers, supported by the CWC, demanded a 40 hour week, it took the combined treachery of their union leaders and the mobilisation of 12,000 troops – again under Churchill’s direction – to break the movement that again had the potential to spread nationally.

Union membership doubled between 1914 and 1920, when it reached 8.3 million. Some two million of this increase were women mobilised to the industrial workforce during the war, although their jobs were often ‘taken back’ when men were demobilised. But the radicalism of the workers movement as a whole was not easily reversed – even the police were on strike in 1919!

After the war – Labour and union leaderships talk left, bosses on the offensive

One method of re-establishing control was rhetorical – in 1918 Labour introduced as Clause 4 of its constitution a commitment to wholesale nationalisation. Another was organisational – the leading sections of the trade union bureaucracy re-set the Triple Alliance first mooted in June 1914 – a promise that miners, train and transport unions would take united action in support of each other as necessary. But while paying lip service to the syndicalist ambition of radical union solidarity, in practice the bureaucracy systematically undermined it. So an ambitious programme for action, voted for by miners’ delegates in January 1919, for a 30 per cent wage increase, a 6 hour day and nationalisation of the mines (with some workers’ control) was corralled by the leadership into support for the Sankey Commission, which produced a report that conceded much of the above but was shelved by the liberal Prime Minister Lloyd George once the danger had receded. Likewise when the government imposed wage cuts on the railway workers in September 1920, JH Thomas was unable to prevent his members striking, but he could prevent the Triple Alliance being invoked.

As the brief post-war boom turned to recession, the mine owners went on the offensive, on 31 March 1921 locking out their workers for refusing to accept wage cuts and an end to the national agreements. The miners of the MFGB called on the support of the Triple Alliance, but despite mass meetings of enthusiastic workers – including 10,000 bus workers in London, two weeks later on Friday 15 April – solidarity action was called off by JH Thomas of the NUR and Robert Williams and Ernest Bevin of the Transport Workers. The day was thereafter dubbed ‘Black Friday’ by anyone with class consciousness, and left the miners to fight on alone for three months then fall to defeat.

Despite very high levels of strike activity (86 million days of strike action in 1921, surpassed only by the year of the General Strike) many of the radical shop stewards of wartime had been victimised or, in some cases, incorporated into officialdom. This weakened the ability of the rank and file to act independently of the trade union bureaucracy. And in tacit recognition of its betrayal, the TUC leadership reorganised its Parliamentary Committee into a General Council to ‘coordinate industrial action’.

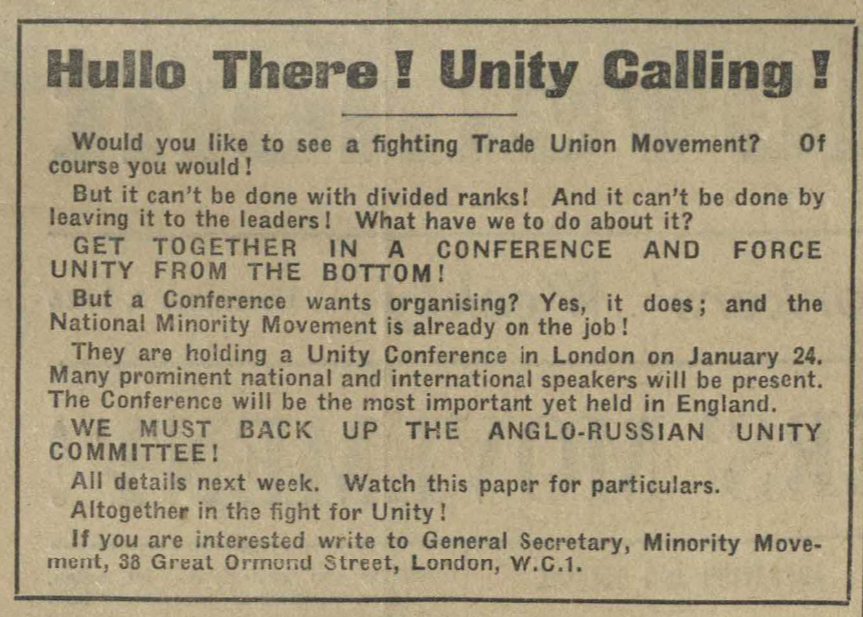

Communist Party looked to left union officials

This posed a crucial question for the British Communist Party, newly established in summer 1920 from an uncomfortable merger of the existing far left. How would it apply the ‘vanguardist’ model first nurtured through illegal clandestine organising in Tsarist Russia to conditions of established trade union legality? The advice from Moscow – persuasive but not yet dictatorial in its authority over its sister parties – was to affiliate with the Labour Party and to build a National Minority Movement within the unions. Both would provide forums and networks in which the few thousand communists could persuade and mobilise wider layers of socialists and militants.

While rightly trying to avoid sectarian irrelevance, the trouble was that the strategy did not have a clear and consistent analysis of the left bureaucracy, who were entrusted to transmit rank and file radicalism into the General Council despite all the evidence to the contrary. Communist leader Harry Pollitt claimed that ‘A few leading men, if they would only see the opportunity before them, could at this moment achieve anything by coming together on a clear definite programme and rally all the active elements in the trade unions.’ It was this attitude that would lead the Communists to call first for ‘more power to the General Council’ (of the TUC) and later even ALL power to it, as if it were the reincarnation of the Russian Soviets. The National Minority Movement (NMM) had the rhetorical trappings of a rank and file movement, but was a Broad Left in practice.

This tendency was strengthened from 1924 by the formation of the Anglo-Russian Trade Union Unity Committee. This initiative, begun during Labour’s brief minority government, was an attempt by an increasingly Stalinised USSR to normalise international relations, and by British trade union leaders to give themselves left cover. It was very successful at the latter aim, with the NMM increasingly defending bureaucrats willing to use radical phrases while undermining militancy in practice.

Meanwhile the Labour government had more former public schoolboys (8) than trade unionists (7), and those it did have were of the dubious quality of JH Thomas. The Prime Minister, Ramsay MacDonald was nicknamed ‘Biscuits’ for the peerage he had delivered to Sir Arthur Grant of McVities, apparently in return for £40,000 and the use of his flash car. The government’s attitude to industrial action differed little from its Tory predecessors, with troops mobilised in response to a three day dock dispute and the use of the Emergency Powers Act to quell a transport strike also actively considered. Ernest Bevin, then TGWU leader who would later wield such powers himself as wartime Minister of Labour, commented, ‘I only wish it had been a Tory government in office. We would not have been frightened by their threats. But we were put in the position of having to listen to the appeal of our own people.’ Such is the song of reformism.

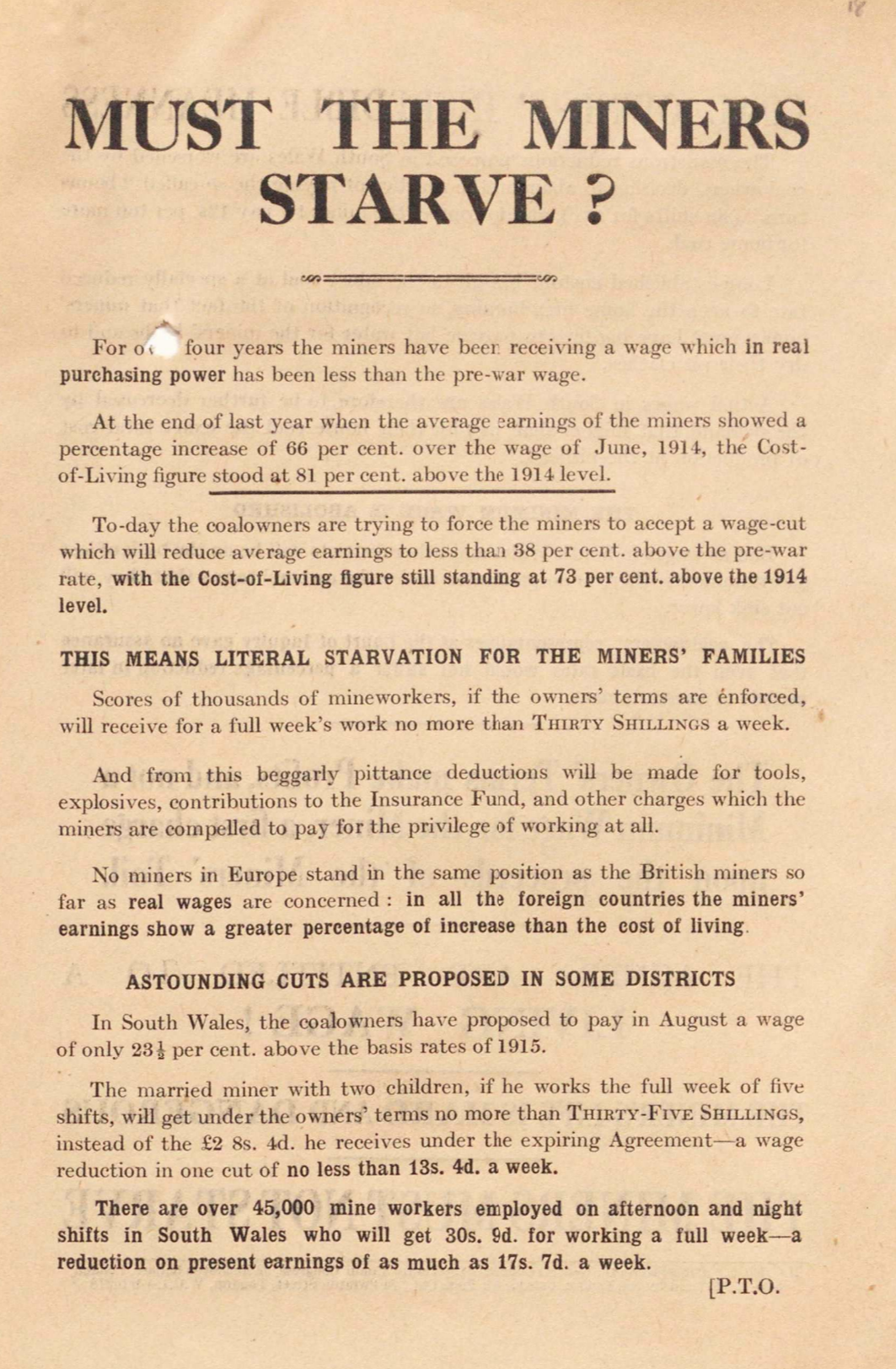

1925 – mine bosses demand wage cuts

Did the subsequent Tory government spur the bureaucrats to action? Not exactly. But the deterioration of the mining industry precipitated a conflict that they would struggle to avoid, especially with the memory of Black Friday still so fresh. A combination of increased foreign competition and Chancellor Winston Churchill’s re-establishment of the Gold Standard – driving up the cost of exports – led the mine owners to demand increased sacrifices from the workers for the sake of their profits. On 1 July 1925 they laid out their terms, to take effect by the end of the month – severe wage cuts of 13.5 per cent, an end to the guaranteed minimum wage and of national agreements. If anyone was under the illusion that this was just a sectional concern for the miners, it was dispelled by Tory Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin’s frank statement that ‘All the workers in this country have got to face a reduction in wages’. The whole working class was under attack.

The TUC was pressured by grassroots outrage to form a Special Committee and issue instructions to transport and dock workers not to handle any coal from midnight on 31 July. Cabinet papers show that the government took fright but that their retreat was only tactical:

Many members of the Cabinet think that the struggle is inevitable and must come sooner or later… The majority… regard the present moment as badly chosen for the fight though the conditions would be more favourable nine months hence. Public opinion is to a considerable extent on the miners’ side.

So a government subsidy was to be paid to the industry to cover the shortfall caused by the government’s own monetary policy… with the subsidy to expire in nine months.

Red Friday – an armistice, not a victory

This was undoubtedly an important victory for the labour movement, but it was a defensive one – it didn’t address the miners’ longer term aims around nationalisation, working hours, conditions or pay. And it was also clearly a temporary one. As the chair of the MFGB conference said a few weeks later, ‘It is only an armistice, and it will depend largely on how we stand between now and May 1st next year as an organisation in respect to unity as to what will be the ultimate result.’

The government was active in making preparations, giving its full support to a 100,000 strong private volunteer army of scabs, the Organisation of the Maintenance of Supplies. The country was divided into ten districts under Civil Commissioners, posh quasi-Cromwellian Major-Generals who would oversee preparations and recruitment in road, coal, finance and food. A dozen Communist militants were imprisoned for 6 to 12 months. Meanwhile, Baldwin packed the Samuel Commission, which was to report on future plans for the mining industry, with industrialists and bankers. No trade unionists were invited.

Meanwhile, in historian Alan Bullock’s account:

In the seven months between [October 1925] and the crisis at the end of April 1926 which led straight into the General Strike, the full [TUC] General Council did not once discuss what was to happen when the government subsidy came to an end on 30 April nor concern itself with preparations for support of the miners…

The TUC’s Special Industrial Committee took a disastrous ‘watch and wait’ approach. Ernest Bevin later confirmed that the General Council did not draft any plans for the General Strike until 27 April, just a week before its outbreak.

The nine-day General Strike that began on 4 May 1926 was a remarkable display of class conscious solidarity by millions of workers. Despite all the failings of the trade union leadership described above, victory at that point was still possible. But its attainment had been made so much harder by a combination of bureaucratic inertia and confused radical strategies. Ultimately there is no substitute for grassroots activism and solidarity emerges from there, not the maneuverings of trade union officials. Organisation is necessary to discuss, experiment and generalise from best practice, and a clear socialist strategy can help to point out opportunities and warn of pitfalls.

Despite substantial economic, social and cultural changes in the last century, such issues continue to challenge socialists organising today, so Red Friday is worth remembering, for all its warnings.

0 comments